Initiation Rites Guiding Transitions to Adulthood and Beyond

Across many African societies, the transition from childhood to adulthood is marked not simply by age or physiological development, but by elaborate initiation rites. These rituals are structured systems of education and transformation that publicly confirm a young person’s readiness to assume adult responsibilities. Among the Bemba people of northeastern Zambia, the Chisungu initiation ceremony for girls is a prime example of this tradition. The rite not only educates but also socially redefines the initiate, preparing her for womanhood and integration into adult society.

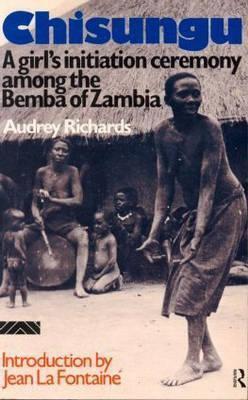

Initiation rites across Africa serve as regulated transitions, rites of passage that mark the movement of individuals from one social status to another. These rituals often include phases of separation, instruction, symbolic ritual, and reintegration, each contributing to the initiate’s transformation. The rites also establish cultural continuity by ensuring that knowledge, values, and social expectations are passed down from one generation to the next. The Chisungu ceremony is one of the most comprehensive and ritualized initiation rites documented in sub-Saharan Africa, practiced by the Bemba people of Zambia. It is reserved for girls reaching puberty, particularly those who have experienced menarche. The ceremony signals readiness for marriage and adult female responsibilities. It typically spans a period of two to four weeks, though the duration may vary by region and family tradition. Ethnographer Audrey Richards, in her classic 1956 work Chisungu: A Girl’s Initiation Ceremony among the Bemba of Zambia, offers a detailed account of the ritual, highlighting its educational and spiritual dimensions.

The initiation begins with seclusion, during which the initiate, called the mukoshi, is taken to a designated hut or house on the edge of the village. She is attended by her banachimbusa (senior women relatives or specialists), who are responsible for conducting the initiation. The seclusion serves as both a symbolic removal from childhood and a practical measure for focused instruction.

During this phase, she undergoes a ritual cleansing and abstains from certain foods and activities. She is taught silence, modesty, and attentiveness. Her daily schedule is controlled, and her body is sometimes marked with white clay, symbolizing purity and readiness for transformation.

Next is the Instruction Phase. This is the core of the Chisungu rite. Instruction is delivered orally, demonstratively, and symbolically. The banachimbusa teach the mukoshi about her body, menstruation, pregnancy, marriage, sexual conduct, and domestic roles. Instruction is not delivered in abstract terms but through songs, dances, clay models, and dramatic enactments. For instance, clay figurines may represent married couples, childbirth, or domestic tools. One widely used model is the three-stone hearth, symbolizing the family triad: husband, wife, and child. The stability of the heart depends on all parts working together, an analogy often used to explain marital cooperation.

Other instructional items include:

● Anthropomorphic clay figures: Used to depict sexual anatomy and intimacy, always taught with seriousness and cultural propriety.

● Cord-weaving and mat-making: Taught as both craft and metaphor for patience and resilience.

● Body postures and gestures: The initiate is trained in appropriate bodily comportment, particularly in relation to elders, husbands, and in-laws.

Instruction often takes place early in the morning or at night, away from public view. Songs are repeated until memorized, and the meanings of symbols are explained carefully. No men are allowed in the instruction space.

Also, a number of ritual dances are performed by the initiate throughout the ceremony, often accompanied by percussive music, call-and-response singing, and symbolic movements. The mukoshi may reenact episodes from her instructional lessons or dance to songs that encode moral teachings.

Certain ritual acts are repeated multiple times to reinforce understanding. For example:

● Cleansing dances: Signifying a break with girlhood and the internal purification required to become a wife.

● Submission rituals: Where the initiate may kneel before senior women as a sign of humility and willingness to learn.

● Feeding ceremonies: Where the initiate is fed by her instructor, symbolizing dependence and then eventual independence.

One particularly significant ritual is the “coming out” dance, which is only performed after the instructors are satisfied that the initiate has mastered her lessons.

The final phase of the rite is the public emergence of the initiate. This is marked by celebration, feasting, and formal recognition of the girl’s new status. She is no longer addressed as a child but as a woman (na-mukoshi), and is eligible for courtship and marriage. During this phase, the girl performs ritual dances publicly. She may wear special clothing and ornaments to signal her transformation. Community elders and guests offer gifts, blessings, and sometimes advice. Songs composed during her seclusion are sung in her honor. Then, the ceremony closes with blessings from elders, who invoke ancestral spirits to protect and guide her in her new life stage.

Chisungu is not a symbolic formality; it is a binding social contract. It affirms the collective’s responsibility toward the initiate and her responsibility to the group. Moral expectations, such as respect for elders, avoidance of promiscuity, marital loyalty, and domestic discipline, are deeply embedded in the instruction. These teachings are reinforced by metaphors, taboos, and expectations clearly explained during the rite.

Importantly, the banachimbusa are not simply instructors; they are guardians of cultural knowledge. Their authority is unquestioned during the ceremony, and their roles are recognized as vital to the community’s integrity. The Chisungu rite thus becomes both an educational system and a ritual form of governance.

In contrast to the Chisungu female initiation ritual, male initiation rites across Africa, such as ulwaluko among the Xhosa or emorata among the Maasai, often emphasize physical endurance, circumcision, and warrior training. These rites typically include extended periods of seclusion and moral instruction on bravery, self-restraint, and community protection. Like female initiation, they serve to socially redefine the initiate and integrate him into adult society. However, their thematic focus tends to be on courage, leadership, and social defense.

The Chisungu initiation rite among the Bemba is a comprehensive process of education, discipline, and identity formation. It moves beyond mere celebration to serve as a structured and sacred system of socialization. Through symbolic ritual and direct instruction, the initiate is shaped into a responsible adult who understands her role in the community. The rite ensures continuity not only in cultural practice but in communal values and moral expectations. In understanding such practices, it becomes clear that African initiation rites are not marginal or exotic customs. They are essential institutions through which societies teach, regulate, and transform. Grounded in lived tradition and sustained by generations of knowledge, these rites remain a powerful guide in the human journey from childhood to adulthood and beyond.

References

- Richards, Audrey I. Chisungu: A Girl’s Initiation Ceremony among the Bemba of Zambia. London: Faber and Faber, 1956.

- Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1969.

- Van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizedom andGabrielle L. Caffee. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey. Traditional Customs and Practices in Africa. Pretoria: New AfricaPress, 2006.

- Krige, Eileen Jensen. The Social System of the Zulus. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter &Shooter, 1936.

Join the Oriire Community

Become a free member to bookmark your favorite stories, join the discussion and personalize your experience.

Share

0 Comments