Introduction

The Zulu people, South Africa's largest ethnic group residing in KwaZulu-Natal, maintain a connection to their ancestors known as amadlozi. This belief system forms the foundation of Zulu society, influencing daily life from understanding fertility and fortune to interpreting misfortune. It creates a worldview where the living remain linked to the "living-dead," shaping their quest for purpose and integration.

Within this framework, Zulu diviners called izangoma (singular: isangoma) serve as conduits to ancestral spirits. They function as the "sole voice" through which the living communicate with, appease, and receive guidance from the amadlozi, thereby influencing individual well-being, community harmony, and understanding of spiritual order. This position grants them spiritual authority that translates into social and political influence within the community. While individuals may engage in personal prayers or offerings, direct interpretation of ancestral messages and effective spiritual intervention require an isangoma's expertise.

Zulu History and Geography

The Zulu people are a Nguni ethnic group of Southern Africa whose history traces back through extensive Bantu migrations. Their origins lie in Nguni communities who migrated down Africa's east coast over centuries, eventually settling in what is now KwaZulu-Natal.

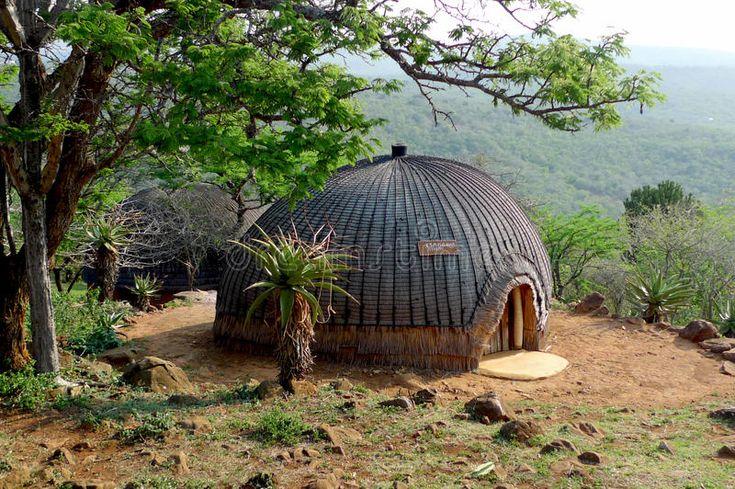

Their heartland is KwaZulu-Natal province, situated on South Africa's east coast. This region, nestled between the Drakensberg mountains and the Kalahari borderland, has been central to their cultural development, providing fertile ground for their communities to flourish.

The 19th century marked a turning point in Zulu history with King Shaka Zulu's rise. Initially a minor clan founded around 1574 by Zulu kaMalandela in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, the Zulu nation transformed under Shaka's leadership. He united what was once a confederation of lordships into an empire through military and social reforms. These included new military tactics, such as the "impi" spear infantry formation, and social reorganization through the ukubuthwa system, which assigned young men to regiments (amabutho). This expansion led to the Mfecane ("Crushing"), a period of conflict and displacement across Southern Africa as Zulu military power reshaped the regional political landscape.

The Zulu nation's strength appeared during the Anglo-Zulu Wars in the late 19th century. Despite ultimate defeat, Zulu forces resisted British colonial powers, achieving victory at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879. These events embedded pride, resilience, and collective identity within the Zulu people..

Amadlozi: The Living-dead

Zulu traditional religion hinges on a belief that recognizes uMvelinqangi ("the first comer-out") or Unkulunkulu (the Supreme Creator, "the greatest one") as the Supreme Being and Creator of all things. While sometimes conflated, uMvelinqangi is also the sky god, manifesting through natural phenomena like thunder and earthquakes.

Most important to their spiritual life are the amadlozi, the ancestors, often called the "living-dead." These ancestors are not worshipped as the Supreme God but regarded as the closest human link to uMvelinqangi, serving as spiritual intermediaries. The term amadlozi derives from dloza, meaning "to care for, keep an eye on," underscoring their protective role over their living descendants. They are also known as abaphansi, meaning "those of the below," reflecting the belief that the spirit world is situated beneath the earth.

Within the ancestral realm, hierarchy exists. Senior ancestors known as amathongo are believed to be custodians of umsamo or isigodlo, the Zulu people's physical and spiritual center. The term amathongo derives from ubuthongo, "deep sleep," referencing their communication through dreams and visions.

Not all deceased elders achieve amadlozi status in a positive sense. Those known for evil during their lifetime are considered idlozi elibi (evil ancestor) and hold diminished status in the world of the living and living-dead, becoming ancestors by blood ties only. To qualify as a benevolent ancestor, one must have lived to old age and conducted their life in an exemplary manner, enhancing the standing and prestige of their family or clan.

Zulu cosmology emphasizes interconnectedness between the human world, spirit world, and natural environment. All living things leave behind "imikhondo" (tracks) and absorb influences from their surroundings, which can be beneficial or detrimental.

The amadlozi are considered a life-giving force, actively involved in the daily lives of the living. They provide guidance, bestow blessings, ensure fertility, grant good harvests, and offer protection. When things go well, the Zulu express that their ancestors are "with them." Conversely, misfortune, illness, and spiritual imbalances are attributed to ancestral anger or neglect, a state known as ulaka lwabaphansi. When misfortune strikes, ancestors are said to be "facing away."

Becoming a Zulu Diviner (Isangoma)

Becoming a Zulu diviner, or isangoma, is not a chosen profession but a sacred calling, an ubizo, from the ancestors themselves. This calling often manifests as an "initiation illness" known as ukuthwasa. The symptoms can be severe and varied, including psychosis, headaches, stomach pain, shoulder and neck complaints, shortness of breath, swollen feet, and general illnesses that defy conventional medical treatment. From a Zulu cultural perspective, these symptoms are not viewed as mere mental or physical ailments but as signs of ancestral possession and spiritual awakening. Failure to respond to this divine summons can lead to further illness, misfortune, and consequences for the individual and their family.

Once the calling is recognized and confirmed by an experienced iisangoma, the initiate, known as an ithwasane or ithwasa, embarks on a training period under the guidance of a mentor, or gobela. This journey can last from several months to many years. It is described as a "metaphysical transformation," involving a symbolic "death" of the initiate's old identity (ivuma ukhufa) and their rebirth as a healer.

While both men and women can become traditional healers, the prominence of female diviners is notable, with "most iisangoma are women." It is often women who are credited with bringing the ubungoma (divination vocation) to their in-laws. This prevalence suggests an avenue for women to attain respect, leadership, and influence within Zulu society's spiritual framework, providing social mobility and authority that may transcend conventional gender roles. The divinely mandated nature of the calling legitimizes their authority, as it is perceived as divine imperative rather than personal ambition. This creates dynamics where spiritual power can counterbalance or complement traditional social structures.

It is crucial to distinguish iisangomas (diviners) from inyangas (herbalists or doctors). While iisangomas primarily rely on divination, spirit possession, and direct ancestral communication for healing and diagnosis, inyangas focus on the preparation and application of medicines derived from plants and animals. However, these roles are often complementary, with iisangomas typically diagnosing the spiritual cause of an ailment and then referring the patient to an inyanga for healing.

The Isangoma's Practices and Communication

Zulu isangomas employ a diverse array of methods to bridge the gap between the living and the spirit world, acting as intermediaries for communal and individual well-being. These practices are embedded in Zulu cultural traditions and are central to their role as the sole voice to the ancestors.

One of the primary methods of ancestral communication is spirit possession or mediumship. During a healing session, the isangoma works themselves into a trance state through rhythmic drumming, dancing, and chanting. In this altered state, an ancestor takes possession of their body, allowing direct communication with the patient. Diviners address these possessing spirits as makhosi, a term derived from "chief," emphasizing the authority and power of the ancestral presence. Some diviners are known as "whistling diviners" (umlozi), where ancestral spirits communicate directly through whistling words that are meaningful to the client.

Another method involves divination bones, or dingaka. The isangoma throws these oracle bones, and the ancestors control how they land. The isangoma then interprets the arrangement of the bones, discerning messages related to the patient's afflictions, the requirements of the ancestors, and the necessary solutions to restore balance. This process is central to their diagnostic capabilities.

Dreams and visions are also channels through which ancestors communicate, providing revelations, guidance, and warnings to both the isangoma and the patient. Interpreting these symbolic messages forms a part of an isangoma's training, with initiates often gathering before sunrise to analyze their dreams with their mentor.

Various ritual elements facilitate communication. The burning of imphepho (a sacred incense) and the use of snuff are common practices to invoke and interact with ancestral spirits. Drumming is also integral to summoning ancestors, creating the energetic environment for their presence.

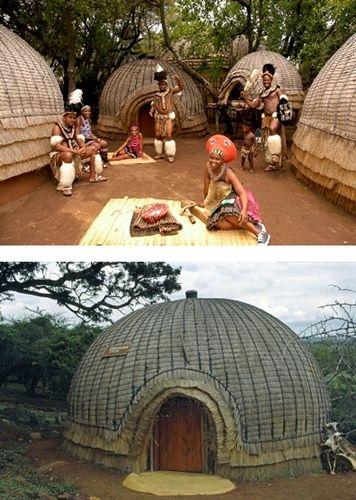

Traditional healers typically conduct their practices in a sacred healing hut known as an indumba. This space is consecrated to the ancestors, often positioned in a corner facing east, adorned with patterned cloths, and illuminated by incense and a lit candle. The indumba serves as an environment conducive to achieving the altered states of consciousness necessary for spiritual connection.

The isangoma employs a holistic healing approach, addressing physical, emotional, and spiritual illnesses comprehensively and symbolically. They are often regarded as "soul doctors" because their role extends to diagnosing imbalances or afflictions within a person's spiritual essence. Diagnosis is performed through divination, which reveals the underlying cause of illness or misfortune. Once the cause, which is frequently attributed to ancestral anger, witchcraft (abathakathi), or ritual impurity, is identified, isangomas prescribe remedies. These treatments can range from dietary modifications and herbal preparations to the identification of personal taboos and the expulsion of malevolent spirits.

A aspect of Zulu healing, as mediated by isangomas, is its focus on answering the why behind illness and misfortune, rather than solely the what or how. Misfortune and illness are rarely seen as random occurrences; they are interpreted as signs of spiritual disharmony, ancestral displeasure, or the malevolent influence of witchcraft. This diagnostic approach means that healing is not merely about alleviating symptoms but about addressing the root moral, social, and spiritual imbalances. This understanding of causality grants isangomas a role in maintaining not only individual health but also broader communal well-being and social order. Their interventions aim to restore harmony between the afflicted individual and the spirits that may be causing their problems.

Gudiance, Blessings and Direct Intervention

Zulu ancestors are not distant, passive entities but are believed to be actively involved in the lives of the living. They offer guidance, protection, direction, advice, and warnings, serving as protectors against sorcery and other malign influences.

The ancestors bestow blessings that contribute to prosperity and well-being, including fertility and bountiful harvests. When a family experiences good fortune or prosperity, it is interpreted as a sign that their ancestors are "with them." The importance of amadlozi is evident in life events such as marriage. Marital rituals are viewed as pivotal for "resuscitating the ancestral kraals of his ancestors," ensuring that the union is "graced, sanctioned and protected by the ancestors." This underscores the belief that ancestral approval is essential for the success and harmony of new family units.

Conversely, when misfortune strikes, it is understood as a signal of ancestral displeasure, prompting an urgent need for appeasement and correction of behavior. This often necessitates rituals, sacrifices, and seeking an isangoma's diagnosis to understand the specific transgression that has angered the ancestors.

Stories and ethnographic accounts provide illustrations of these direct interactions and the influence of ancestors:

The Zulu folktale, "The Spirit in the Tree," is an example of ancestral guidance and protection manifesting through natural phenomena. The narrative tells of a young girl, grieving her deceased mother and suffering under the cruelty of her stepmother. In her despair at her mother's grave, a stalk grows from the earth, transforming into a tree. The tree, through the rustling of its leaves, whispers to the girl, assuring her of her mother's presence and offering nourishing fruits. When the stepmother destroys the tree, a pumpkin emerges, then a stream, each providing sustenance and comfort. Ultimately, the spirit's intervention leads the girl to a kind hunter who recognizes her plight and marries her. This story highlights the presence of ancestors within the natural world and their active intervention in times of hardship, showcasing their role as guardians.

More contemporary ethnographic accounts reveal direct ancestral intervention in personal aspects of life, such as sexual identity. Studies indicate that some izangoma engaging in same-sex relationships report that this orientation is not a personal choice but is "imposed" or "forced" by their ancestral guide, depending on the ancestor's sexual attraction when they were alive. This demonstrates a direct level of ancestral influence on individual lives, even in areas often considered private or personal. This also illustrates how traditional beliefs can offer frameworks for understanding and legitimizing diverse identities within the community, as these experiences are attributed to divine mandate rather than personal preference.

Beyond specific narratives, ancestors are believed to be present in the homestead and should be kept informed of any life events, such as changes in residence, work, or fortunes. Oral traditions, including genealogies and praises (izibongo), are vital for remembering and honoring ancestors, with violations of these traditions potentially leading to ancestral punishment, such as drought or famine.

Lessons from the Ancestors

Ancestral interactions serve as a moral compass for the Zulu people, embedding ethical standards and guiding moral conduct in daily life. Ancestors are believed to punish the living for failing to adhere to community ethical standards and to remind them of their duty to live a moral life. Misfortune, illness, or spiritual imbalances are understood as direct consequences of moral transgression, neglect of kinship duties, or deviation from prescribed norms.

Zulu oral traditions, particularly folktales, play a role in transmitting these moral lessons across generations. These narratives teach children and adults about the distinction between good and evil, desired qualities, and appropriate behavior, guiding them on how to navigate life's challenges. For instance, many human tales in Zulu tradition arise from a wrong that must be rectified or a break in social harmony that needs restoration, with the resolution often emphasizing the triumph of good over evil.

Zulu proverbs further encapsulate this ancestral wisdom and moral guidance, with proverbs like "You can learn wisdom at your grandfather's feet, or at the end of a stick," which emphasize the importance of heeding the advice of elders to avoid painful consequences learned through personal mistakes. "You cannot know the good within yourself if you cannot see it in others", promotes empathy and the recognition of positive qualities in others as a means of building self-esteem. The proverb "When you bite indiscriminately, you end up eating your own tail" advises thoughtful action and planning to avoid self-inflicted harm, especially when acting out of anger or fear. These proverbs are not mere sayings but condensed forms of ancestral wisdom, serving as guides for ethical living.

The ancestral realm is linked to the Zulu concept of justice. Zulu literature, including moral stories and detective stories, features themes where "good triumphs over evil" and "justice prevails." Wrongdoers are punished, and disturbances in social harmony are corrected. Ancestors are understood to "provide the sanctions for the moral life of the nation and accordingly punish, exonerate or reward the living as the case may be." This framework implies a system where divine oversight ensures accountability for actions, reinforcing the moral order of society.

The Zulu worldview is shaped by the concept of ubuntu, which signifies humanism, love (uthando), and respect (inhlonipho). It emphasizes the interconnectedness of all life and the belief that "all realization is only possible through human relationships." Ancestral reverence is a core component of maintaining harmony (ukulungisa) within the community and strengthening generational consciousness, forging a link between the living, the living-dead, and the yet unborn. This concept extends beyond individual well-being to encompass the entire community and its relationship with the spiritual and natural worlds.

The relationship between the divine, ancestors, and humanity in Zulu cosmology is one of interdependence.

Conclusion

Zulu diviners are irreplaceable and exclusive intermediaries between the living and the amadlozi. Their authority to diagnose misfortune, offer guidance, and facilitate appeasement is legitimized by their sacred calling, often manifesting as spiritual illness, and their training through ukuthwasa. The prominence of female diviners highlights avenues for female leadership and influence within the Zulu and their role as the "sole voice" to the ancestors, centralizing spiritual interpretation, ensuring an authoritative narrative that underpins social order and individual well-being.

The ancestral wisdom, conveyed through the diviners, oral traditions, and proverbs, continues to shape Zulu morality, justice, and their understanding of the divine-human relationship. It fosters a worldview where individual well-being is linked to communal harmony, ethical conduct, and connection to the spiritual realm. The ancestors, through their active agency, serve as enforcers of social norms, providing a framework for ethical governance and social cohesion. The isangoma, as the enduring voice to the ancestors, remains a figure in navigating life's challenges, interpreting the cosmic order, and upholding the balance of the Zulu cosmos, ensuring that ancient wisdom continues to guide present and future generations.

References

- Mfulawoziwilderness.com. "The Songoma." . https://mfulawoziwilderness.com/the-songoma/

- ResearchGate. "The Concept of Healing in the Zulu Worldview Within the Context of Traditional Religion." . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391805341_The_Concept_of_Healing_in_the_Zulu_Worldview_Within_the_Context_of_Traditional_Religion

- SouthAfrica.net. "African Ancestors and Amadlozi." . https://southafrica.net/za/en/travel/article/african-ancestors-and-amadlozi

- ThoughtCo. "Zulu (South African) Proverbs." . https://www.thoughtco.com/zulu-south-african-proverbs-43389

- Traditional Healers of Southern Africa. Wikipedia. . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Traditional_healers_of_Southern_Africa

- Ukuthwasa. Wikipedia. . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ukuthwasa

- Wikipedia. "History of South Africa." . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Africa

- Wikipedia. "Zulu People." . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zulu_people

- Zulu Traditional Religion. Wikipedia. . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zulu_traditional_religion

Share

0 Comments