So the sun drops behind the horizon like a coin into a slot machine, and suddenly the sky becomes a canvas painted in reds and oranges that would make a sunset photographer weep with envy. Around a crackling fire, shadows dance like backup performers in some cosmic theatrical production. An elder settles into storytelling mode, becoming the umlobi wezinganekwane—which roughly translates to "the person who will now monopolize the conversation for the next several hours."

Zulu izinganekwane served multiple functions; entertainment, moral instruction, and a guide to navigating a world where the supernatural wasn't some distant concept but rather your particularly difficult neighbour who might curse your crops if you forgot to invite them to dinner.

The Zulu worldview operated on the premise that the human and spirit worlds weren't separated by some vast chasm but were more like adjoining apartments with exceptionally thin walls. Every mundane Tuesday could suddenly become complicated by supernatural interference, which made daily life rather like living in a cosmic sitcom where the laugh track was provided by ancestral spirits.

At the center of this cosmological organization chart sat Unkulunkulu, "the very old one"—a title that suggests either great wisdom or simply that nobody could remember when he'd actually started the job. He emerged from Uhlanga, a great swamp of reeds, which makes him perhaps the only deity whose origin story involves what essentially amounts to premium wetland real estate.

From this botanical headquarters, Unkulunkulu proceeded to create humans, animals, and the natural world, then thoughtfully provided humanity with a user manual covering hunting, fire-making, and agriculture. He was occasionally confused with Umvelinqangi, the thunder and earthquake specialist whose name means "he who was in the very beginning"—though whether this refers to temporal precedence or simply arriving early to meetings remains unclear.

While some suggested that belief in a supreme deity came courtesy of European missionaries (the theological equivalent of cultural contamination), traditional practitioners maintained they'd always known about a supreme being who outranked even Unkulunkulu. This created a hierarchy that would make corporate management consultants proud.

More immediately relevant to daily life were the ancestors, or Amadlozi—also known as Abaphansi, "those of the below," which sounds rather like a supernatural homeowners' association. These weren't your garden-variety deceased relatives but active guardians operating from a parallel universe. They provided guidance and protection when properly maintained but could deliver misfortune with the efficiency of a well-oiled bureaucracy if neglected or disrespected.

This established a relationship with the supernatural that functioned on strict reciprocal terms. The ancestors maintained constant performance reviews of the living, and their management style could be described as "involved." The moral frameworks embedded in folklore served as an employee handbook for navigating this complex relationship and maintaining harmony across family, community, and cosmic levels.

Hlakanyana: The Professional Troublemaker

Enter Hlakanyana, Zulu folklore's most celebrated problematic character—a trickster whose job description apparently read "chaos coordinator" with benefits including "exposing societal weaknesses through questionable means."

Unlike deities with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, Hlakanyana operated in what scholars diplomatically term "undistinguished grey areas"—professional speak for "everywhere he wasn't supposed to be." He was a semi-human dwarf born into royalty, which already suggested that someone in the cosmic HR department had made some interesting hiring decisions.

His colleagues in the trickster department included Nogwaja, the clever hare, and Chakijana, the slender mongoose. Together, they formed a supernatural consulting firm specializing in exposing human gullibility through hands-on demonstration.

Hlakanyana's operational methods combined unbridled appetites with keen intelligence, making him rather like a very small, very hungry management consultant. His legendary food obsession drove him to elaborate schemes that would make modern con artists take notes. In one documented case, he convinced villagers that their dogs had stolen meat by framing them so thoroughly that the men beat their wives and children. This particular story serves as an early example of how misinformation campaigns can destabilize communities, though Hlakanyana's motivations were considerably more straightforward than modern political operatives.

Another tale features him outsmarting a monstrous creature by convincing it that his leg was a tree root—a deception that succeeded primarily because the monster had apparently never seen either a leg or a tree root before. This story functions as a commentary on the dangers of hiring creatures with poor observational skills for security positions.

The most disturbing story in Hlakanyana's portfolio involves his colleague Chakijana offering babysitting services to a lioness. The mongoose systematically killed and cooked her cubs, then served them to the mother while maintaining an elaborate charade that they were still alive and simply napping. The horror here wasn't just the trickster's actions but the lioness's failure to notice that her children had become lunch. This tale operates as what might be called "preventive education"—teaching audiences to maintain situational awareness even when convenient childcare presents itself.

These stories weren't designed to celebrate Hlakanyana but to use him as a diagnostic tool. By violating every social norm with cheerful efficiency, he exposed the community's vulnerabilities. His tales served as a moral mirror, reflecting back the potential for chaos that existed within supposedly civilized society. The lesson wasn't that intelligence was dangerous, but that it was morally neutral—a powerful tool that could be employed for construction or destruction with equal effectiveness.

The trickster's function was essentially that of a quality control inspector for social systems. His stories taught vigilance, critical thinking, and recognition of moral ambiguity. They suggested that evil often arrived wearing a friendly face and offering apparently beneficial services, and that the line between victim and accomplice could be thinner than most people preferred to acknowledge.

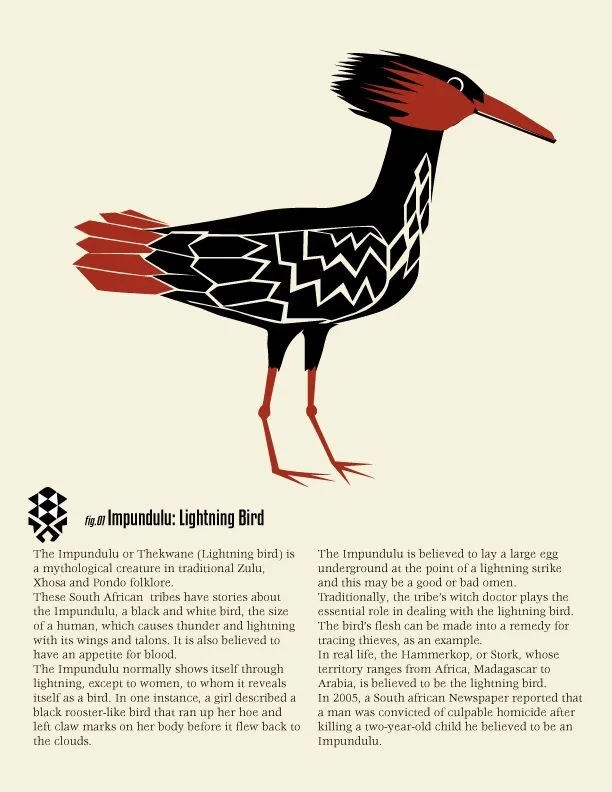

Impundulu: The Lightning Consultant

While Hlakanyana operated as a freelance chaos agent, the Impundulu represented organized supernatural services—specifically, the kind you hired when you needed someone cursed with professional efficiency.

Known as the "lightning bird" or "bird of the heavens," the Impundulu was described as a creature roughly person-sized, usually black and white, though some accounts mentioned iridescent plumage that suggested either supernatural origins or an exceptionally good grooming routine. It could also appear as a black rooster, which was presumably less intimidating until it started summoning thunderstorms.

The Impundulu's shape-shifting abilities included transforming into an attractive young man, a talent it used for seduction. However, its true nature was vampiric, possessing what sources describe as an "insatiable appetite for blood"—making it rather like a supernatural combination of dating app catfish and vampire, which seems redundant but apparently served a market need.

Unlike Hlakanyana's chaotic freelancing, the Impundulu operated as a service provider for witches and witch doctors. It was dispatched on specific missions to deliver illness, bad luck, or death to designated targets. This represented supernatural services moving from cottage industry to professional contracting, complete with clear service agreements and measurable outcomes.

The belief that misfortune was often "people-induced" was foundational to Zulu society, and the Impundulu provided a concrete explanation for life's various disappointments. Rather than accepting that sometimes things just went wrong for no particular reason—a psychologically unsatisfying conclusion—the lightning bird offered the comfort of knowing that your troubles had been personally arranged by someone who disliked you enough to hire supernatural assistance.

The creature's near-immortality added to its professional credentials. It was immune to gunshots, stabbing, drowning, and poison, with fire being its only known weakness. This gave it better workplace safety statistics than most occupations, though it did suggest that its clients needed to keep fire insurance current.

The Impundulu's origin stories often traced back to internal social friction, particularly jealousy between co-wives in polygamous households. This made sense from a psychological standpoint—when your husband's other wife got better treatment, it was more emotionally satisfying to believe she'd hired supernatural assistance than to accept that perhaps your husband just liked her more.

By providing a physical manifestation for feelings of envy and hatred, the lightning bird myth externalized very real social anxieties. The fear of the creature served as a deterrent against the kind of internal discord that could lead to witchcraft accusations and community breakdown. It was essentially a supernatural human resources department, managing interpersonal conflicts through the threat of divine intervention.

The Contrast of Both

The two archetypal figures represented different approaches to supernatural customer service. Hlakanyana embodied unpredictable chaos with educational benefits, while the Impundulu offered targeted malevolence with reliable results.

Hlakanyana's chaos served diagnostic purposes, exposing societal flaws through practical demonstration. His victims typically contributed to their own downfall through gullibility, greed, or poor judgment. The trickster's actions, while destructive, ultimately provided learning opportunities for those observant enough to take notes.

The Impundulu, by contrast, was a tool of deliberate malice, representing the weaponization of supernatural forces. Its victims were chosen not for their moral failings but for their unfortunate position as someone's enemy. Where Hlakanyana taught self-reflection, the Impundulu taught external vigilance.

Both served the same fundamental purpose: providing frameworks for understanding moral complexity. Trickster tales encouraged communities to examine their own weaknesses and correct them before someone else exploited them. Lightning bird myths taught communities to identify sources of internal conflict and address them before they escalated to supernatural intervention.

The difference lay in their approach to responsibility. Hlakanyana's stories suggested that people often created their own problems through poor decision-making. The Impundulu's myths acknowledged that sometimes problems were genuinely inflicted by others, but warned that allowing internal conflicts to fester created conditions where such supernatural services might be employed.

And so the tale lives on.

The tales of Hlakanyana and the Impundulu represent more than historical curiosities—they constitute a functioning moral operating system that has served Zulu communities for generations. By embodying intelligence's chaotic potential and malevolence's organized threat, these figures provide a framework for understanding ethical complexity that remains relevant in contemporary contexts.

They teach wariness of both external dangers and internal weaknesses that could lead to social breakdown. They suggest that evil often arrives through familiar channels—the helpful neighbor, the attractive stranger, the convenient solution to persistent problems. They acknowledge that intelligence and supernatural power are morally neutral tools that can serve construction or destruction depending on their application.

Most importantly, they recognize that moral education requires more than abstract principles—it needs concrete examples, memorable stories, and frameworks that help people navigate ambiguous situations. The supernatural consultants of Zulu folklore continue to offer services in this regard, providing wisdom passed down by firelight that remains illuminating in electric times.

These stories remind us that the line between victim and accomplice, between wisdom and gullibility, between necessary vigilance and destructive paranoia, requires constant navigation. They suggest that the most dangerous threats often come from within communities rather than outside them, and that maintaining social harmony requires both individual responsibility and collective awareness.

The ancient wisdom embedded in these tales continues to resonate because the fundamental challenges they address—how to live ethically in complex relationships, how to maintain community bonds while respecting individual agency, how to balance trust with vigilance—remain constant across cultures and centuries. The supernatural consultants may have updated their service offerings, but their core business remains unchanged: teaching humans how to be human in a world where moral choices have consequences that extend far beyond immediate results.

References

"African-American Folktales for Young Readers." HCPL.net. Last modified March 1, 2025. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://hcpl.net/blogs/post/myth-of-tricky-legend-what-anansi-means-to-the-world/

"Zulu Religion." Encyclopedia.com. Last modified August 13, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/zulu-religion

"Zulu Religion." Heritage Tours and Safaris. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.heritagetoursandsafaris.com/zulu-religion/

"Zulu Traditional Religion." Wikipedia. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zulu_traditional_religion

Evans, Zteve T. "African Folklore: The Lightning Bird." ztevetevans.wordpress.com. May 18, 2016. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://ztevetevans.wordpress.com/2016/05/18/african-folklore-the-lightning-bird/

Hexham, Irvin. "Lord of the Sky-King of the Earth: Zulu traditional religion and belief in the sky god." Journal for the Study of Religion. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/4p8y05/what_religious_beliefs_did_the_zulu_have_when/

"Lightning Bird." Wikipedia. Last modified August 3, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lightning_bird

Lynch, Patricia Ann and Jeremy Roberts. African Mythology, A to Z. Infobase Publishing, 2010. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uhlakanyana

"Myth of Tricky Legend: What Anansi Means to the World." HCPL.net. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://hcpl.net/blogs/post/myth-of-tricky-legend-what-anansi-means-to-the-world/

"Mythlok: Impundulu." Mythlok. n.d. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://mythlok.com/impundulu/

"Mythlok: Zulu." Omnika.org. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://omnika.org/myths/zulu

"Oral Literature in Africa." Journal of African and Asian Studies. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233168172_The_function_of_songs_in_the_performance_of_Zulu_folktales

Prins, J. "The trickster in Zulu folktales." Sabinet African Journals. n.d. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA10231757_238

"South African Vampiric Lightning Bird." Reddit. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/mythology/comments/dijbqq/impundulu_south_african_vampiric_lightning_bird/

"Stories in IsiZulu to Learn the Language." Superprof. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://www.superprof.co.za/blog/zulu-stories-to-learn-isizulu/

"The Lightning Bird: The Hamerkop." Medium. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://medium.com/wildlife-trekker/the-lightning-bird-the-hamerkop-a7b844aaafd4

"The Sausage Tree and Zulu Mythology." Writing to be Read. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://writingtoberead.com/2022/06/22/dark-origins-african-myths-and-legends-the-zulus-part-3-zulucreationmyth-sausagetree/

"Uhlakanyana." Fictional100.wordpress.com. n.d. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://fictional100.wordpress.com/tag/hlakanyana/

"Uhlakayana." Wikipedia. n.d. Accessed August 20, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uhlakanyana

We appreciate your contribution.

Join the Oriire Community

Become a free member to get the monthly roundup, unlock more challenges, comment on articles and bookmark your favourites

Share

0 Comments