There's a striking wooden mask with lustrous dark wood and refined features that catch your eye in a museum. It’s beautiful and mystical, right? But here's the fascinating part – among the Dan people of west-central Côte d'Ivoire and northern Liberia, these aren't just carved objects sitting behind glass. They're called Ge or Gle, and they're believed to house living spirits that actively shape society.

These mask-spirits are more than museum pieces, think of them as social agents working overtime to keep communities harmonious, settle disputes, and maintain order within men's fraternal societies. They are peacekeepers with serious judicial powers. This exploration dives into how these entities function as both spiritual guardians and very practical problem-solvers in Dan society.

Meet the Dan People

The Dan people (also known as Yakuba in Côte d'Ivoire and Gio in Liberia) inhabit the mountainous, humid regions where these two countries meet. Their lush, historically isolated terrain has been their cultural laboratory for centuries. As part of the Southern Mande linguistic group, they share roots with neighboring peoples like the Gere and Mano.

Oral traditions tell us the Dan migrated from present-day Guinea and Mali, bringing with them a reputation as fierce warriors who regularly clashed with groups like the Kru. But the early 1900s changed everything, when the Liberian government established administrative controls, the Dan entered a new era of peace.

This shift from warfare to peace was spiritual. The emergence of the go (leopard) society, centered on peacemaking spirits, seems to be a direct response to this new reality. It's a perfect example of how traditional systems adapt: when external pressures demanded stability, Dan institutions evolved to deliver it through mask rituals designed for a post-conflict world.

Traditional Dan society operates without a strong central authority. Instead, social cohesion comes from shared language and intermarriage networks, villages split into quarters, each led by extended families under "quarter chiefs" chosen for age or assertive personalities and village chiefs work with elder councils who wield real decision-making power.

Economically, it's straightforward: men handle agriculture, hunting, and fishing while women manage households and vegetable plots. Historically important in working and trading have given way to modern labor in diamond camps and rubber plantations.

But here's the spiritual foundation that makes everything else work: the Dan see the world split between "village" (human-controlled space) and "bush" (uncontrolled wilderness). They believe in Zlann or Xra, a supreme creator who doesn't require direct worship. Instead, a spiritual power called Zu or Du acts as a mediator, contacted through dreams.

Dreams aren't random for the Dan – they're direct divine messages. This makes dream-inspired masks inherently sacred and authoritative, crucial for their roles in social enforcement and peacemaking. It's a system where individual spiritual experience directly serves community well-being. All creatures possess immortal spirit souls (du), and some remain bodiless as bush spirits in forests. These spirits need appeasement to participate in village life – often through masquerade. Despite Christian influence, most Dan people maintain their traditional beliefs.

What Is Ge/Gle?

Ge or Gle refers both to the physical mask and the invisible forest spirits believed to inhabit them during performances. These spirits live in the wilderness and can only enter human society through masquerade rituals.

The birth of a Dan mask is pure spiritual drama. A gle-zo (initiated person) receives a dream where a spirit appears, requesting a mask and providing exact specifications – costume details, dance moves, musical accompaniment, even the name. This isn't human creativity; it's divine commissioning. The elder council must approve the creation based on this spiritual blueprint.

Once carved, the mask becomes spiritually charged and stays powerful whether worn or not. An elder performs a ceremony allowing the spirit to inhabit the mask and activate its power. But here's the maintenance requirement: humans must sustain the gle's presence through regular offerings of rice, palm oil, or sacrificed chicken blood.

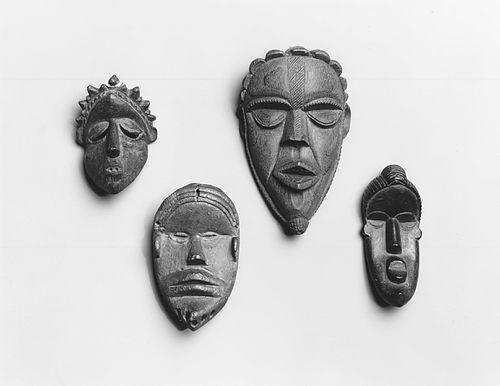

Dan masks are visually stunning: dark, lustrous oval faces with concave surfaces, protruding mouths, high-domed foreheads, and narrow eyes. Crafted from wood and decorated with fiber, pigment, fur, feathers, monkey skin, iron nails, copper alloy, and sacrificial materials. Dan sculptors enjoy high community status, receiving rewards like women, food, and elevated social standing for talents considered divine gifts.

The diversity is remarkable – each mask possesses unique characters, preferences, dance styles, and speech patterns. Wearers embody these qualities during the performance. Masks can transform over their lifetime, gaining sacred status and assuming bigger community roles. This adaptability keeps the tradition dynamic rather than static.

Key Dan Ge/Gle Mask Types and Functions

Deangle: Narrow, almond-shaped eyes and feminine attributes create gentle, peaceful spirits. They collect food for initiation camps and represent beauty, benevolence, teaching, and nurturing.

Bu gle: Protruding tubular eyes and bold angles mark these masculine "war gle" (named after gunshot sounds) designed to frighten.

Gunyege: Oval-faced masks used in racing competitions, believed to help wearers win races.

Ge Gon (Bird Mask): Blending human faces with bird beaks, complete with small oval eyes and voluminous beards. They symbolize wisdom and world connections, originally educational/regulatory but now often entertaining with bird-like movements.

Gle Wa (Judicial Mask): Respected masks elevated from other types to settle village disputes or larger area conflicts.

Wompomeingle: Commands respect as "accusation" gle, judging and settling disputes for whole villages or larger areas.

Gunlagle: Village quarter judges who can ascend to town-wide judicial roles.

Ma Go (Miniature/Passport Mask): Small family mask copies (6-20 cm) carried on bodies or possessions for protection, traveler identification, divination, oath-taking, and communal protection in secret societies.

Kagle: Features triangular reliefs, used in joyful celebrations while testing war-time loyalties and assessing community support for chiefs.

Zapkei: Fire-watching masks that prevent domestic fire spread.

Gleben: Justice masks appear white when spirits are calm, black when agitated, brought from storage when judicial functions are needed.

Inside the Boys' Club: Masks in Men's Societies

Men's "secret societies" (Gor or Poro) form the backbone of Dan social and political life. These aren't just ritual clubs – they're the primary vehicles for transmitting cultural knowledge and norms, serving as fundamental pillars of social reproduction and control. They govern spiritual and social order, functioning as important community power sources under elder oversight. Only initiated members can interact with certain masks.

Masks play central roles in male initiation rites marking boys' passage to manhood and guiding them throughout life. This initiation period prepares boys to encounter spirit world mysteries while internalizing rules, social ideals, values, and ethics essential for adult Dan men. The Dean gle mask, for example, dances at male initiation ceremonies, gracefully collecting food for forest camp initiates. This comprehensive education ensures generations understand their responsibilities for maintaining Dan social order.

The integration of masks into hierarchical systems governing political and religious life demonstrates how spiritual authority and political governance intertwine in Dan society. The go master heading the go society holds and safeguards masks in sacred huts, symbolizing their immense power. Elder councils assisting village chiefs also control men's societies.

This creates a system where secular and sacred authority reinforce each other. Masks embodying powerful spirits provide supernatural sanction for elder and chief decisions, making their authority less challengeable from purely human sources. This spiritual-political fusion through masks creates robust governance and social control systems. Miniature masks displayed at men's society meetings serve as sacred objects for collective protection and oath administration to new initiates.

Judge, Jury, and Spiritual Executioner

Dan masks serve as social control agents, playing roles in law enforcement, conflict resolution, and social order maintenance. They're believed to be "incarnate spiritual beings capable of rendering unbiased judgments." The concealment of human identity behind masks is principal to this function, ensuring impartiality and legitimacy while removing personal elements that could complicate judicial processes in close-knit communities.

This "unidentity" enables enforcement of verdicts that might be difficult for humans to deliver "eye-ball to eye-ball," preventing personal vendettas by dissociating judgment from specific individuals.

Authority masks actively mediate dispute settlements, with wearers channeling spirits for mediation. They're called upon to settle "legal wrangles" and "disputes that cannot be settled by ordinary authorities." The glewa judicial mask can be elevated to settle disputes for entire villages or larger areas. Some masks gained such peacemaking renown they were "requested across great distances and ethnic boundaries."

This demonstrates an almost international judicial authority where certain masks' efficacy and spiritual power overshadow local affiliations, therefore contributing to regional stability. The wompomeingle "aaccusatio gle” judges and settles disputes for whole villages or larger areas, commanding widespread respect. Similarly, the gunlagle "village quarter gle “ adjudicates quarter disputes, with wise gunlagle ascending to town-wide judicial roles. Masks like the gleben justice mask are specifically brought from storage when judicial functions are required.

Masks can also denounce spell-casters, with their judiciary function instilling healthy fear among populations.

While specific detailed accounts of Dan judicial processes aren't extensively documented, general African conflict resolution methods offer parallels. These typically involve parties stating grievances without interruption, victims disclosing offense impacts, and offenders explaining behavior, with community members exposing denial. Traditional teachings, counseling, and spiritual assistance through prayer are integral. Outcomes frequently involve symbolic or material restitution. Masked figures embodying impartial spirits facilitate processes aimed at reconciliation and communal harmony restoration.

Masters of Social Regulation

Dan Ge/Gle masks serve as pervasive social regulation instruments, actively maintaining community norms and moral values beyond direct judicial roles. They're instrumental in instilling values and societal norms among younger generations, ensuring cultural practice continuity. Masks also police and control traditional ceremonial life, preserving established traditions.

Mask functions extend to subtle social commentary and psychological management forms. The kagle mask historically tested war-time loyalties through rough performance behavior revealing community support for chiefs based on reactions – sophisticated social diagnostics without direct confrontation. Some masks teach through negative behavior, even making fun of people with deformities. Rather than being purely derisive, this practice assuages feelings of being cast out and alleviates tensions surrounding such individuals.

This indicates a deeper psychological function, using humor or satire through masks to address sensitive social issues, integrate marginalized individuals, and release communal tension, reinforcing social cohesion through ritualized social therapy.

Masks fulfill significant educational purposes beyond formal initiation, transmitting cultural knowledge and ethics throughout communities. The Dean gle mask, for example, specifically handles teaching and nurturing roles.

Protective roles of Ge/Gle masks highlight holistic social order understanding encompassing not just human interactions but environmental, health, and spiritual threat management. Masks are sought for protection, healing, and ensuring bountiful harvests. Zapkei masks specifically intervene to prevent domestic fire spread during dry seasons, safeguarding communities from natural disasters. They also guard against sorcery problems and contribute to healing processes.

Masked spirits appear at funerals to honor the deceased, facilitate afterlife transitions, and offer protection and guidance to the living. This broad "social enforcement" scope underscores the comprehensive Ge influence on daily life, where community well-being intrinsically links to spiritual harmony and benevolent spirit intervention.

Showtime: When Performance Meets Power

Masquerade is the primary, most dynamic means by which Ge/Gle spirits manifest and participate in human affairs. During performances, mask wearers are believed to "give up their own being," allowing "spirit identity to take over." These performances are often highly theatrical entertainment festivals, historically serving as village ceremonies, though today they are also performed for important visitors.

Ge performance is a holistic, multi-sensory experience designed to fully immerse participants and convey spiritual presence. Masks complement full-body costumes typically adorned with raffia, feathers, and fur, disguising wearer's human identity and enhancing spiritual manifestation.

Music is considered the "fuel" driving gle performance, with ensembles often comprising drums, gourd rattles, and mixed choruses. Rhythms and melodies known as getan accompany songs, clapping, and dancing, creating vibrant soundscapes. Music serves dramatic functions, emphasizing emotional states and enhancing audience pleasure and movement awareness.

The dance features components ranging from graceful glides (for Dean gle) to complex bird-like motions (for Ge Gon masks). Dancers move with subtle, quick foot turns, bending at waists and turning shoulders, contributing to overall spiritual embodiment.

Verbal elements are crucial – each mask possesses distinct speech patterns interpreted by accompanying attendants. Performance lyrics can include gossip, news, and social criticism, often delivered competitively. This combination of visual, auditory, and kinetic elements creates powerful, immersive ritual environments where the "invisible" becomes tangible, reinforcing spirit presence beliefs and amplifying mask social and judicial function impacts.

Audience interaction is vital to masquerade. While audience members know humans are behind masks, they consciously accept spirit presence. Their responses, ranging from fear to joy, depend on perceived spirit visit purposes. Performances are often highly interactive, with community members gathering, singing, clapping, and dancing along, fostering collective experiences. Sometimes staging is composite, keeping audiences "constantly on the move" as attention draws to various dramatic action pockets.

While prominent Ge masks are worn by male performers (gle-zo) for social control and initiation, women play significant and "preponderant roles" in many theatrical entertainment festivals. Women actively participate as audience members, performing songs and dances accompanying maskers, often assisting in costume creation, and sometimes providing their own clothing for female figures.

Dan women have their own societies similar to Mende Sande society, utilizing masks (like Sowei masks) for initiating young girls into womanhood, and teaching domestic skills and sexual etiquette. The Deangle mask, though danced by men, represents feminine ideals and beauty, illustrating complementary rather than exclusionary gender dynamics in Dan ritual life. This balanced, distinct distribution of ritual power and responsibility between genders ensures both contribute to overall community social and spiritual well-being.

Why These Masks Still Matter Today

Dan Ge/Gle mask-spirits represent a multifaceted cultural phenomena. Far from mere artistic objects, they're living embodiments of ancestral and bush spirits, serving as crucial intermediaries between the spiritual and physical worlds. Their creation, initiated by dreams and sustained by ritual care, establishes dynamic spiritual economies underscoring the community's deep connections to the supernatural.

Within intricate men's fraternal society frameworks, these mask spirits function as an indispensable social order. They're central to young men's initiation, transmitting core social ideals, values, and ethics, ensuring Dan cultural identity continuity. Critically, Ge/Gle masks are powerful peacemakers and social enforcers, embodying unbiased judgment transcending human biases. Their ability to resolve conflicts, enforce laws, and mediate disputes across ethnic boundaries highlights their unique, effective roles in maintaining communal and regional harmony.

Beyond judicial functions, they act as broad social regulators, providing educational guidance, offering protective interventions against various threats, and serving as ritualized social commentary and psychological release forms.

Masquerade performances, total art forms integrating costume, music, dance, and verbal elements, serve as vibrant arenas where these spirits manifest. Audience active participation and spiritual presence acceptance underscore these rituals' profound impacts. Women's significant, distinct ceremonial roles further demonstrate complementary gender dynamics contributing to Dan society's holistic well-being.

Dan Ge/Gle masks' relevance continues to lie in their dynamic nature and capacity to adapt to changing social, political, and global contexts. They're not past relics but active participants in living traditions, continually evolving while retaining central places in shaping Dan identity. The mask-spirits testify to interplays of art, spirituality, and social governance – living legacies continuing to define the Dan people.

References

- "African Art - Dan: The Dan Populations of West-Central Côte d'Ivoire and the Forest Region of Northern Liberia, Known as Yacouba, Produce Masks Associated with the Initiation Ceremonies of Young Boys." Art-africain-traditionnel.com

- "African Masks and Masquerades." New.artsmia.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan." Britannica.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan Bird Masks." Africadirect.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan Ethnic Group Social Structure Traditional Beliefs." En.wikipedia.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan Ge Performance: Masks and Music in Contemporary Côte d'Ivoire." Everand.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan Mask, Côte d'Ivoire or Liberia." Sothebys.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan People." JoshuaProject.net. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Dan People - Wikipedia." En.wikipedia.org. Accessed June 29, 2025..

- "Face Mask (Go Ge or Go Glih)." Metmuseum.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Gunyege Face Mask." Metmuseum.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- Harley, George Way. Masks as Agents of Social Control in Northeast Liberia. Cambridge, Mass.: The Museum Collection, 1950.

- "How an Antique Dan Mask Inspired a Contemporary South-African Artist." Duendeartprojects.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "The Journey of the Dan Mask to Dan Dwelling." Medium.com. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Mask (Dean gle)." Chazen.wisc.edu. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Mask: Face Covering." Britannica.com.

- "Masking in Mende Sande Society Initiation Rituals." Cambridge.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Miniature Mask." Metmuseum.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "The Aesthetics of Performance in African Festivals: The Omabe Masquerade Example." Researchgate.net.

- "Traditional African Masks." En.wikipedia.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.

- "Traditional African Religions." En.wikipedia.org. Accessed June 29, 2025.