Every year on August 1, Emancipation Day is observed across the Caribbean and parts of the former British Empire. It marks the date in 1834 when the Slavery Abolition Act officially took effect, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved people in British colonies, from Jamaica to Barbados, from Trinidad to Guyana. The day is one of celebration and reflection. In places like Barbados, parades and cultural festivals are held. In Jamaica, church services and state addresses commemorate the end of legal bondage. In Canada, particularly in Ontario, August 1 is recognized in honor of the Underground Railroad and the history of Black settlement.

In the United States, Juneteenth has emerged as the primary date of remembrance, marking the end of slavery in Texas on June 19, 1865. Haiti, where the enslaved freed themselves through revolution in 1804, views freedom as a conquest rather than a gift.

Although August 1 unites former colonies under a shared abolition legacy, its meaning is not universal. In the Caribbean, Emancipation Day is a national event. In Africa, it is largely unobserved. Instead, emancipation evokes silence, discomfort, or confrontation. It forces a deeper question: what is freedom to those who are still unfree?

Fractured Kingdoms and Broken Homes

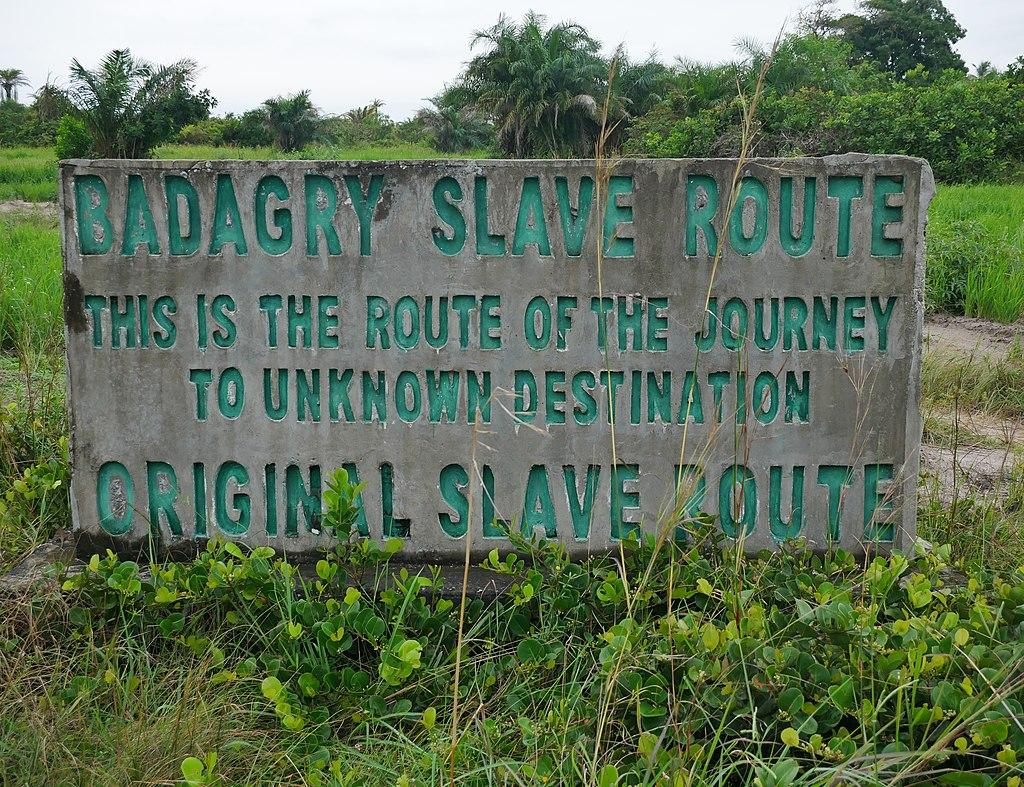

The coastline of southeastern Nigeria tells more than a story of trade. It holds the memory of betrayal. In towns like Esuk Mba, enslaved men and women once stood in long lines under the burning sun, waiting to be sold. They were not marched to the coast by Europeans alone. Local chiefs, regional warlords, and middlemen played active roles, exchanging captives for gin, guns, or cloth. The market flowed toward Calabar, one of West Africa’s busiest slave ports. It remained active until the British banned the transatlantic trade in 1807 and formally abolished slavery in 1833.

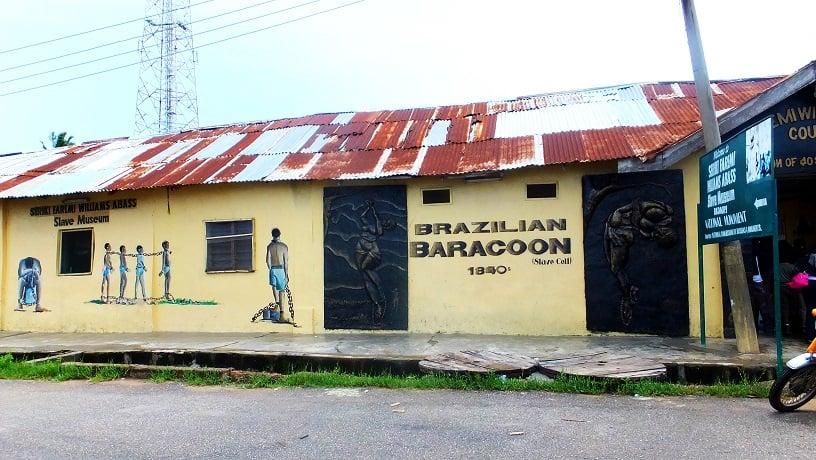

This betrayal came not only from rulers. It also came from those who had once worn the chains. One of the most unsettling examples is Abass Ifaremilekun Fagbemi, later known as Seriki Abass. He was a native of the Badagry region and was captured in the 18th century by a Dahomean slave trader during one of the regional wars between Dahomey and the Egba. Taken to Brazil and sold as a servant, he eventually gained his freedom. Rather than return as a liberator, he came back as a business partner to his former master and helped run the same system that once held him captive.

In the early 1840s, Seriki Abass built a slave barracoon in Badagry containing forty cells. There, other Africans were locked up, sold, and shipped away. Today, that site operates as a museum. It stands as a permanent reminder that some of the very people who suffered under slavery later became merchants of the same misery.

Inland from the coast, in communities such as Akpabuyo, village griots still speak of the day their ancestors disappeared. The ships may have left, but the trauma never did. The memories of empty farmsteads, broken families, and ecological decline have lingered for generations. The slave market at Esuk Mba eventually closed. What it represented, however, never truly left.

Caste Systems and the Aftermath of "Freedom"

The end of colonial slavery did not put an end to social exclusion. Across many West African societies, longstanding systems of hierarchy and marginalization continued to shape daily life even after the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. In southeastern Nigeria, two of the most enduring examples are the ohu and osu caste systems. Their persistence raises difficult questions about the limits of emancipation and the nature of freedom in African contexts.

The Ohu were traditionally domestic slaves within Igbo-speaking communities. Unlike chattel slaves in the Atlantic world, ohu were often absorbed into households and could sometimes attain a measure of social integration over time. The Osu, by contrast, were not enslaved but were ritually segregated. They were people dedicated to deities or shrines and considered spiritually unclean. This status made them untouchable in many areas of life, including marriage, leadership, and religious participation.

It is important to be clear that neither the Ohu nor the Osu systems were direct products of the transatlantic slave trade. These classifications existed prior to European contact and were rooted in local cosmologies, social contracts, and religious beliefs. They reflected internal systems of control and status, not colonial impositions. However, the presence of European missionaries, traders, and administrators did not challenge these structures in any meaningful way. In some cases, they reinforced them, either through misunderstanding or selective accommodation.

Christian missionaries often targeted the Osu for conversion, treating them as spiritually available but socially separate. Colonial governments, while officially neutral on local customs, frequently relied on traditional rulers and systems of indirect rule that preserved caste divisions by default. The result was that caste structures remained intact even as slavery was legally abolished.

In 1956, the Eastern Nigerian House of Assembly passed a law outlawing caste-based discrimination. On paper, the legislation marked a turning point. In practice, little changed. Today, in many communities, descendants of Ohu and Osu still face barriers to full social inclusion. Families often investigate a suitor’s ancestry before agreeing to marriage. Certain ceremonial roles remain closed to people of “impure” lineage. Political success does not always translate into cultural acceptance. A person may hold elected office, yet be barred from performing key rituals in their hometown.

These practices are quiet but powerful mechanisms of exclusion. In private conversations, entire families are judged by associations with ancient categories. What appears to be cultural continuity is often a form of social policing, disguised as respect for the past.

This ongoing exclusion challenges the idea that emancipation was ever fully achieved. The abolition of slavery in British colonies in 1834 and the later outlawing of caste discrimination in Nigeria did not dissolve the systems that determined who belonged and who did not. The persistence of caste suggests that freedom cannot be measured only by the removal of legal chains. It must also be judged by the presence or absence of full social belonging.

It would be inaccurate to describe Ohu and Osu as consequences of the slave trade. However, ignoring their continued impact in the aftermath of slavery would miss a deeper truth. Some forms of ‘unfreedom’ existed before Europeans arrived, and some remain long after they left. These are not colonial wounds, but they are part of the legacy that emancipation failed to heal.

This is why Emancipation Day, though rooted in colonial history, should provoke a broader reflection. It should not only commemorate what ended but also question what survived. When entire lineages are still considered inferior by tradition, when exclusion is practiced in the name of culture, and when silence protects inherited injustice, then the promise of freedom remains incomplete.

Freedom must be more than a historical milestone. It must be made real in social practice. Until a person’s ancestry no longer determines their value in the eyes of their community, the work of emancipation is not done.

The architecture of slavery across Africa

Across West Africa, the physical remnants of slavery remain. Old barracoons, slave markets, and holding cells still stand in places like Badagry and Calabar. These sites once held lives and loss, but today they often sit in silence. Few are maintained with care. Most are underfunded, under-visited, or simply overlooked.

In many communities, these places blend into the landscape. Schoolchildren pass them without knowing their significance. Local governments rarely invest in preservation. National education systems avoid the subject or treat it as distant history. What should be spaces of reflection often become forgotten corners.

This neglect is not only about limited resources. It reflects a deeper discomfort. Remembering slavery in Africa is difficult, not just because of what was done to African people, but because of what some African communities did to each other. Memory becomes risky when it requires facing betrayal, complicity, and silence passed down through generations.

As a result, remembrance survives mostly in private acts. A few elders pour libations. Local custodians retell stories when asked. These moments matter, but they remain isolated. There are no public holidays or state ceremonies. The weight of memory falls on individuals, not institutions.

This silence carries consequences. Without structured remembrance, communities lose the tools to ask hard questions. They lose the chance to name what was taken, and who took part. What remains is not peace, but avoidance. And without memory, the idea of freedom becomes shallow. It no longer asks what was broken or what needs repair.

Emancipation is not just about what ended. It must also be about what remains. If communities do not preserve their history, others will shape it for them. If they avoid the past, they risk repeating its exclusions in new forms.

Pan-Africanism, Heritage, and the Business of Memory

The idea of Pan-Africanism once promised moral clarity and political solidarity. In the mid-19th century, Edward Wilmot Blyden envisioned a unified Africa, reborn through the return of diasporic knowledge and cultural pride. Later, figures like Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. Du Bois called for the descendants of the enslaved to reconnect with their ancestral continent. Kwame Nkrumah gave the vision political teeth, insisting that Ghana’s independence in 1957 was meaningless unless it sparked a continental revolution. Freedom, they argued, was not just national but African and collective.

Yet more than sixty years after Ghana’s independence, the dream of continental unity remains largely rhetorical. African nations continue to be fragmented by colonial borders, language blocs, and economic self-interest. Regional bodies like ECOWAS and the African Union often issue declarations that fail to influence realities on the ground. Political leaders use Pan-Africanism as a symbol in speeches, but rarely in policy. When it comes to caste discrimination, historical accountability, or internal divisions, silence returns.

Meanwhile, a new kind of Pan-Africanism is being practiced through what some call heritage tourism. Across West Africa, especially in Ghana, Senegal, and Nigeria, sites associated with the transatlantic slave trade have become pilgrimage destinations for African Americans and members of the diaspora. They come to places like Cape Coast Castle, Gorée Island, and the Seriki Abass Barracoon in Badagry, hoping to reconnect with ancestral roots, mourn the past, and find spiritual or cultural closure.

In October 2023, during the 4th Door of Return festival in Badagry, the Nigerian government and Lagos State welcomed twenty-seven descendants of formerly enslaved Africans back to Nigeria. According to the Nigerian Tribune, the event featured cultural ceremonies, tours of historic slave sites, and plans by the returnees to invest in the local economy and build a “Diaspora Palace” in Badagry. NIDCOM Chairperson Abike Dabiri-Erewa celebrated the symbolic homecoming, declaring it a powerful step in reconnecting lost generations to the motherland. Dr. Julius Garvey, son of Marcus Garvey, was present and given a Yoruba name by local royalty, calling the experience a long-awaited return.

Events like these have emotional and symbolic power. They draw headlines and foster reconnection. But they also risk turning memory into performance—polished for tourists, detached from local reckoning. While the state welcomes diaspora visitors with ceremonies and red carpets, many indigenous descendants of slaves in Nigeria still face subtle exclusion and caste-based stigma. Roads leading to slave forts are paved, while discrimination within villages remains unaddressed.

Memory, in this sense, becomes an export, curated for international consumption while internal truths are avoided. Pan-Africanism is turned into a product, marketed in festivals and cultural displays, yet disconnected from the lives of people who still live with slavery’s residue. The contradiction is clear: descendants of the enslaved return in search of belonging, while local communities struggle with wounds no one has named. True Pan-Africanism cannot be built on curated tours or symbolic gestures alone. It requires structural honesty. It demands that African societies look inward, not just outward—that they confront their internal divides, dismantle caste ideologies, and re-integrate those once ostracized. Until then, Pan-Africanism risks becoming nostalgia with a passport stamp.

Freedom Demands More: The Work Ahead

Across West Africa, the remnants of slavery are not lost. They are visible, often weathered but still standing. In Badagry, the barracoons remain. In Calabar, the slave huts still line the old quarters. The shrines and tunnels of Arochukwu, once used by the Aro Confederacy to traffic captives, are still visited by curious students and cautious tourists. On Gorée Island in Senegal, the House of Slaves faces the ocean, its Door of No Return turned into a point of reflection for thousands each year.

These sites hold the weight of a history that cannot be undone. Yet the way they are remembered varies. In some places, preservation efforts are limited to symbolic rituals or occasional festivals. In others, these sites are marketed for tourism, polished for visitors but disconnected from the daily lives of nearby communities. The memory lives, but often in fragments—spoken in ceremonies, echoed in museum plaques, yet left untouched in national policy and education.

Still, there are signs of resistance to forgetting. In Badagry, community members host annual commemorations, not for spectacle, but to honor the lives once held in chains. In Calabar, local historians advocate for the protection of neglected structures tied to the slave trade. In Arochukwu, conversations have begun about how to reconcile the region’s spiritual heritage with its historical complicity. On Gorée Island, descendants of the enslaved return each year seeking closure and connection, though the island itself struggles to balance heritage and truth.

These efforts matter, but they are not yet a movement. Political leaders attend ceremonies but rarely support deeper institutional reckoning. Local memory keepers carry the burden of history without the tools to transform it into shared responsibility. The silence surrounding complicity, the reluctance to name what happened and who took part, keeps the continent from moving forward.

So what does freedom mean today? It is not a monument or a holiday. It is not a speech or a festival. Freedom becomes real when a community chooses truth over pride, when memory is not just something inherited but something acted upon. It is seen when former slave sites are preserved with care, not as tourist attractions, but as spaces for education and reflection. It is present when children are taught that history includes both resistance and betrayal—and that healing requires naming both.

Emancipation Day, wherever and however it is observed, should not be a moment of closure. It should be a call to account. It should ask whether the past has been faced honestly, whether justice has been imagined beyond ceremony, and whether the promise of freedom has reached all corners of society.

What if every community with a history of trafficking acknowledged it publicly? What if schoolchildren in Arochukwu were taught what the Ibini Ukpabi shrine once represented? What if Badagry’s barracoon became not just a museum, but a national site of moral reckoning? What if the Door of No Return in Senegal became a door of truth, not only for the diaspora, but for those still living in its shadow?

These questions cannot be answered by ritual alone. Nor can they be solved by avoiding the discomfort they bring. Remembrance must be honest, not curated. Reckoning must be active, not symbolic.

We protect divisions inherited from the past and call them culture. We avoid hard truths and call it respect. Then we wonder why the promise of freedom still feels unfinished.

But if, even briefly, we choose to tell the full story—not just of what was suffered, but of what was done—then perhaps we begin to recover what emancipation was meant to deliver.

Until then, the chains may be gone, but the silences remain. And in those silences, true freedom still waits.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_Nigeria

- Campbell, John. “The Legacies of Slavery in Nigeria’s Igboland.” Council on Foreign Relations, October 16, 2019. https://www.cfr.org/blog/legacies-slavery-nigerias-igboland

- Global Press Journal. “History of Atlantic Slave Trade Chronicled by Museums, Monuments in Badagry, Nigeria.” Global Press Journal, October 21, 2020. https://globalpressjournal.com/africa/nigeria/history-atlantic-slave-trade-chronicled-museums-monuments-badagry-nigeria/

- Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani. “Nigeria’s Slave Descendants Prevented from Marrying Who They Want,” September 13, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54088880

- Sayer, Faye. “Localizing the Narrative: The Representation of the Slave Trade and Enslavement within Nigerian Museums.” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 10, no. 3 (August 18, 2021): 257–82. doi:10.1080/21619441.2021.1963034

- Tribune Online, “NIDCOM, LASG Welcome 27 Descendants of Nigerian Former Slaves Back Home.” October 21, 2023. https://tribuneonlineng.com/nidcom-lasg-welcome-27-descendants-of-nigerian-former-slaves-back-home/

- Daily Trust, “Ibini Ukpabi: The Temple of Judgment That Serves as Slave Route.” April 30, 2021. https://dailytrust.com/ibini-ukpabi-the-temple-of-judgment-that-serves-as-slave-route/

- Premium Times. “Badagry Celebrates International Day For Slave Trade Remembrance,” August 24, 2012. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/97575-badagry-celebrates-international-day-for-slave-trade-remembrance.html?tztc=1

Share

0 Comments